Today we’d like to introduce you to Mike DeHoff. They and their team shared their story with us below:

The Returning Rapids Project started initially as a loose-kniot group of river runners who noticed changes in Cataract Canyon – a 41-mile-long stretch on the Colorado River just downstream of the confluence of the Green and Colorado in the heart of Canyonlands National Park. When the reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam, Lake Powell, was full 60% of Cataract Canyon and its rapids were drowned.

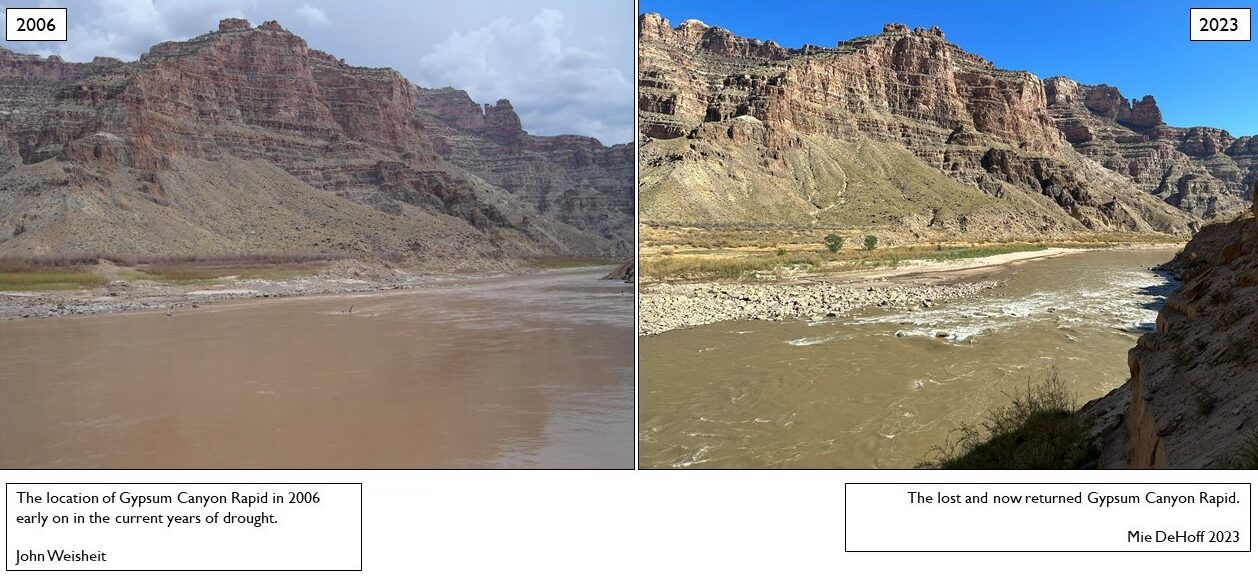

Starting in the early 2000s, Lake Powell receded and changes started to happen in Cataract Canyon. Rapids and other features of the canyon were re-emerging as the river returned to areas that were thought lost under the waters of Lake Powell. “When and where will the next rapid come back?” Was the early question that a ragtag group of river runners set out to answer. This question propelled them into a great adventure that entailed using historic photos and other pre-Glen Canyon Dam information to try and understand how a river and its ecosystem can recover from the effects of a Dam.

In 2019, the Returning Rapids Project research group ran its first science trip. Inviting people from the University of Utah, the United States Geologic Survey, and other scientists launched a study of rates of change. “I have studied geomorphology my whole life, yet here I am and things are changing faster than I could imagine, right before my eyes, right in my own backyard.” Was the impression that was left on one of the University of Utah scientists.

As the research effort grew, it became apparent that the general public was also curious about the changes the team was studying. Through publishing trip reports and an annual publication known as the Field Binder, the team was able to communicate what they were seeing. Field Binders used historic photos, and repeat photography, and detailed the findings of modern-day scientific methods to communicate the rates of change and ecosystem recovery. One of the simple goals was to try and tell the story of what the team was seeing through the simplest language possible.

During 2020-2022 effects of climate change on the Colorado River were causing Lake Powell to further shrink. There was great concern about the river and its water supply in the west. More rapids were coming back in Cataract and the team started to get lots of queries from the press: theThe New Yorker, NPR, The Washington Post, and more.

In the face of the threats of climate change, what the Returning Rapids Project was showcasing was called a silver lining in the face of a crisis. As more science trips and partnerships with universities grew, so did the research. From the fieldwork, scientific papers were published and greater understandings of the rates of change were recorded.

In 2022, in order to find a comparable river system, the group started also doing research trips on the Lake Powell-affected areas of the San Juan River. Partnerships grew further and Fort Lewis College from Durango became involved in the studies. Now in 2024, our research continues. Both the Colorado and the San Juan Rivers are slowly flowing more and more into their canyons. Our team has more and more opportunities to showcase our research. And ours is a project of patience and we are anxious to see what the coming year brings.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way? Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

Ours is a citizen science effort. As our project has grown we have had to navigate many questions around “Who are you guys?” “What are you trying to study?” “What agency did you say you were with?” The project started as a volunteer effort with four core members – Peter Lefebvre, Chris Benson, Meg Flynn, and Mike DeHoff. Everyone had other full-time careers and initially following the changes in Cataract was just a hobby.

We would joke that we go on river trips, and take pictures to watch the change. But as we found out, the public also wanted to know about what we were watching – so we started telling the story more. In the history of Glen Canyon, the Glen Canyon Dam, and Lake Powell Reservoir some people feel that the drowning of Glen Canyon was one of the greatest environmental mistakes of our modern times. Other people absolutely love Lake Powell. Like many things in this day and age, things feel polarized and uncertain about how to move forward.

A river like the Colorado carries a lot of sediment. Water in motion can hold sediment suspended in its flow. When a river gets stilled, impounded behind a dam, all the sediment drops out. In the case of Cataract Canyon, this sediment has dropped out over 60 years to cause a massive sediment plug to cover most of the areas in Cataract Canyon. This sediment is the main thing that is impeding rapids coming back in Cataract Canyon. It is also the main byproduct of taking water from the Colorado River and leaving behind its other parts.

One of the big questions that we have started to ask is “Who manages the sediment?” “Who manages the mud?” There is so much focus put on managing and delivering water in the Southwest yet little thought to any byproducts. While it was one thing to back water up behind Glen Canyon Dam for the sake of water, it is another thing to watch the river corridor get covered in mud… and no federal agency is stepping up to manage this issue.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar what can you tell them about what you do?

I am the leader of a research team. Working outdoors in the river corridors of southern Utah takes a broad range of skills. To be able to organize and run trips is one thing, but to work hard to bring together experts from many different fields, scientists, stakeholders, agency staffers, tribal representatives, and journalists takes navigating group dynamics that aren’t that different from running rapids.

One thing I know and consistently see is how much people are impressed by our natural world in Utah. If there is an equalizer and something that humbles people, it is the amazing landscape that surrounds us. I am proud of having the opportunity to take people out into the various research locations and help them understand what we are watching.

Recently I was talking with a friend who is also a very accomplished scientist. She was telling me that she just signed up to give a series of talks about finding hope in the face of climate change. She asked me where I find hope these days. My response was that all I have to do is to go out to our study areas and see how fast the natural world can recover if we only give it the chance – that makes me proud.

Before we let you go, we’ve got to ask if you have any advice for those who are just starting out.

Stay humble and work hard. Try to communicate and act with integrity. Be clear about what you want, what your roles and responsibilities are – and what you expect from others. Follow your curiosities, find your mentors, and as best you can stay even-keeled and aware of the moment you are in. You are in charge of your life – and there are many subtle things that can leave you feeling like you are not in control.

You are wealthy with time and that is one of the most valuable resources so be conscious about how you spend it. Beware the trappings of modern times. Your attention is a commodity and you do have a choice in how you spend it. There is a lot of wonder in the world, and each person has the right to find their own wonder and times of peace in their lives.

My brother always likes to remind me “If you aren’t having fun, you have no one to blame but yourself.” As far as things I wish I knew starting out… Any good adventure always takes a lot of work. Celebrate your accomplishments and always give other people the credit they deserve. Don’t act like you deserve anything, but you might earn or learn a few valuable things along the way.

Contact Info:

- Website: returningrapids.com

- Instagram: @returningrapids

- Youtube: @returningrapids

Image Credits

Image Credits

Elliot Ross, Travis Custer, and Meg Flynn