Today we’d like to introduce you to Nicole Woodbury.

Hi Nicole, can you start by introducing yourself? We’d love to learn more about how you got to where you are today?

My artistic journey began with music. I was exposed to classical music from a very young age. My family was very musical. We all enjoyed singing together and most Sundays with cousins and siblings would gather around a piano to sing, mostly show tunes or religious music. I loved playing the piano and at a young age, when my family moved to England, I had the opportunity to perform for the American Embassy in London and was featured as a young artist on BBC Radio. Music was a huge part of my life. So, when I began to take art classes, much of my work reflected my experiences with music. I was always fascinated with the patterns of music. Later this translated into a fascination for all of the patterns in nature and science as well. Having been raised with a religious and spiritual background, my art work reflects patterns in nature and a deeper spiritual belief that we are purposely, powerfully and divinely made. The care taken in the creation of all of nature was also taken with our creation. Through my work I direct notice to these incredible natural patterns but, I also hope to find deeper meaning and lessons in these pattens. I have found spiritual connections in the constellations of stars, in the marrow of bones, in the neurons of our brains, and in the geological layers of the earth.

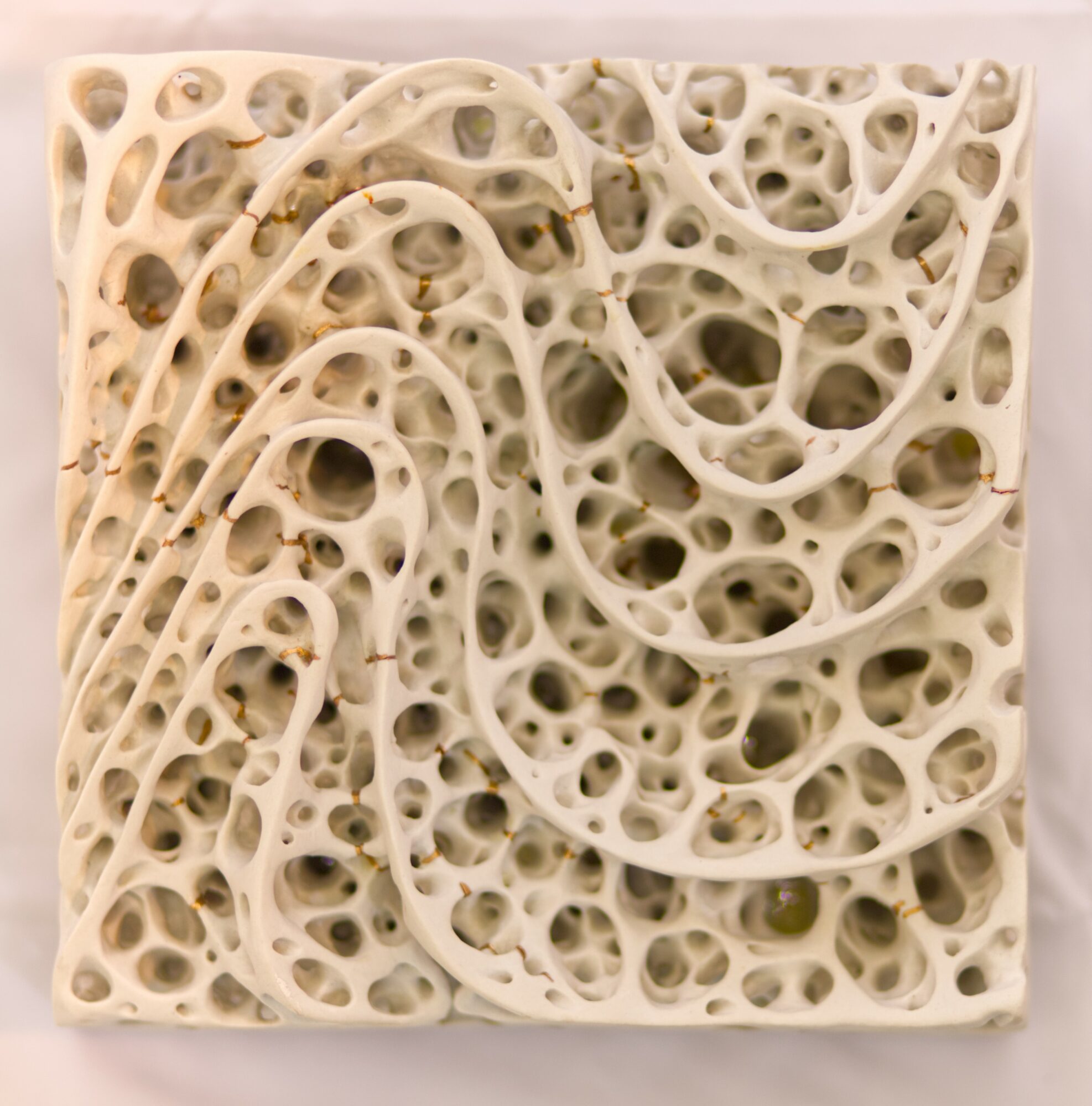

I always had a love of art. When I was a child, I would visit my Grandmother’s house with my siblings and she would give us a stack of corrugated printer paper and freshly sharpened colored pencils. Pristine encyclopedias, found on the shelves of her home became the inspiration for my drawings. When I was in Middle School, my family moved to Europe where I was exposed to an abundance of culture and art. I was naturally drawn to art classes and took them from Middle School into AP Art in High School. I attended BYU and started out applying to the Graphic Design Program. While attending a Study Abroad to Italy, I discovered my true passion lay in creating sculpture so I switched my major, earning a BFA in 3D Studio Art. After graduation, I was determined to keep making art and began creating work in thread and ceramics, specifically carving forms of bone marrow into porcelain. It was then that I had my first child. I now live in North Salt Lake with my husband and 5 children where I continue to make art during a few but dedicated hours of the week.

We all face challenges, but looking back would you describe it as a relatively smooth road?

Like any meaningful journey, mine has had its share of bumps. My biggest struggles have been with indecision and health challenges. In the beginning, my first major choice was between art and music. Once I chose art, I had to decide between studio art and graphic design. I eventually settled on studio sculpture—but then came the question of medium: steel, stone, ceramics, or maybe even glass?

Just as the application deadline for the program was looming—with nothing prepared—I broke my leg in an ice skating class. The left tibia, to be exact. At that point, I had another choice to make: go home and heal or stay and push through the pain to finish my portfolio. I decided to stick it out. Thankfully, I was surrounded by supportive friends and family who became my heaven-sent angels. Since I could only put weight on one leg, welding large forms became nearly impossible alone. They would come with me to the studio and literally hold me steady so I could weld, helping bring the forms from my sketchbook into three-dimensional life using steel rod.

Later, I faced another important decision: whether or not to start having children. I was determined to become a mother without giving up my identity as an artist. I continued to work when I could throughout pregnancy and early motherhood. I believe that being an artist makes me a better mother. The artistic lens of life offers my children a more nuanced perspective. I also believe that being a mother makes me a better artist. My experience though not unique adds a layers of meaning to my work and often allows me space for intentional mindfulness.

These days, while I still focus on sculpture, my artistic approach is far more fluid. I follow what draws me in—letting inspiration guide me—rather than forcing myself into rigid structures. That flexibility has become one of my greatest creative strengths.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar what can you tell them about what you do?

My creative practice is rooted in sculpture, though it spans multiple mediums and methods. I’m particularly known for:

Ceramics — Porcelain Sculpted carvings of bone marrow as used in Within the Marrow of Our Bones and Marrow in the Bones. In Porcelain Sculptures of undulating gyroid-like forms, I utilize techniques like nerikomi (layered colored clay) and kintsugi (repairing cracks with gold), which reflect my fascination with transformation and the beauty of imperfections.

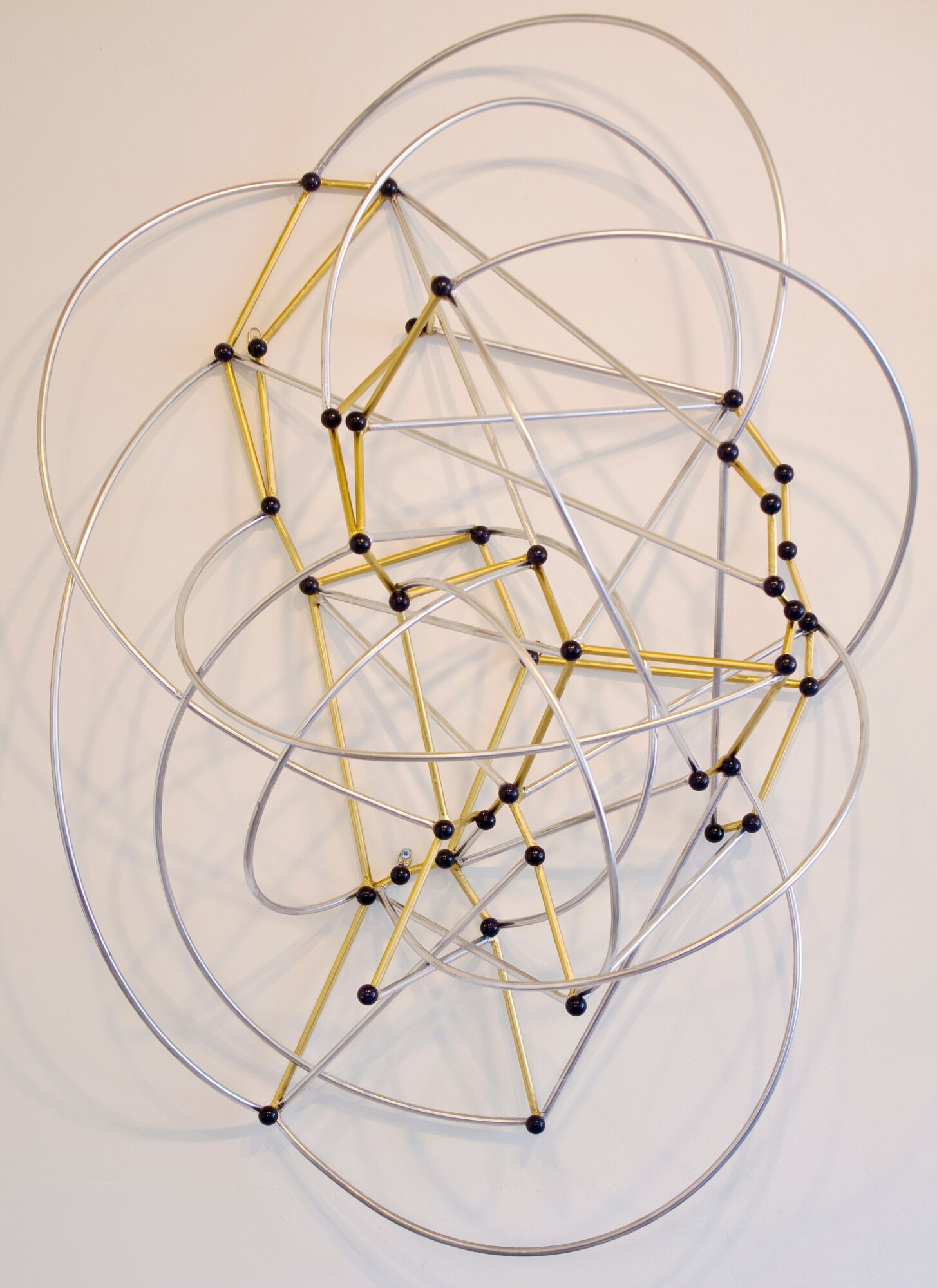

Steel constructions and glass — sculptures that often evoke imagery of constellations and organic networks—works like Orion Constellation Emergence (steel rod and glass) and Boötes Constellation Emergence anchor the cosmos in physical form providing a God’s Eye View of the stars.

Thread paintings —a signature technique I developed by wet-shaping thread and integrating it into abstract mixed-media works, meant to represent neurological expressions.

Fractal Trees — Made of wood or metal. and utilizing fractal dimension of trees, I break down a tree into height and width ratios and build boxes with them. I then use these boxes to build structures based on the form of trees.

What truly sets my work apart is its strong foundation in science and mathematics. My sculptures often represent fractals, neurons, constellations, or geological formations. There’s almost always a tie to an “-ology”—biology, cosmology, geology—because I’m fascinated by how ordered systems can reflect universal truths. I draw inspiration from natural structures—fractal tree systems, neural pathways, geological strata. Each piece is a meditation on both the macro and the micro: from the vast lines of rock layers (Line Upon Line II) to the microscopic webs of neurons.

My art captures a sense of awe and wonder— blending the beauty of mathematical and scientific elements with creative expression. My work is underpinned by faith and a reflection on our place in the universe; I believe that the care used to design the Heavens and the Earth, was used to design each of us.

What has been the most important lesson you’ve learned along your journey?

I would say that the most important lesson I’ve learned along my journey is that all of creation has an ugly phase. Creation tends to have a beginning middle and end and most people give up somewhere around the middle. The First Phase is a honeymoon phase. It’s new and exciting and you are involve with the idea of it. You make plans and sketches, trying to prepare to make your creation. Then you get down to work, starting to mold it with your materials. And inevitably you think you should be further along than you are. Eventually you will get to a point where the materials aren’t doing what you thought they should be doing and at this point and it stats to look ugly. This is what I call “The Ugly Phase.” We often give up during the ugly phase of creation. I get it, it’s painful! The piece is a nightmarish monstrosity instead of the beautiful dream we had in our mind. But what a beginner doesn’t know is that creation always reaches the ugly phase. Anyone who creates anything, knows this phase, though we don’t see many pictures of it, or read many books with it because it’s the third draft out of twenty. It’s the 14th run through of a music piece out of 50. It’s the underpainting. It’s usually ugly and it’s really hard to look at. It’s like an awkward teenager. We are horrified by what we have created. But a master knows, it’s just not finished yet. I do not claim to be a master of my medium, but I do claim to be persistent. You have to keep going. Every form of creation that I know of, goes through an ugly phase. I promise you, even in a master’s hand, it is there, it had to go through an ugly phase. Like when I use clay, for example, the whole time I am hand building, I am also sensing the strength of the clay, applying pressure to strengthen it where needed, but also allowing for it to stretch which weakens it. It’s a balance between flexibility and stability. It’s constantly changing with gravity and moisture level and pressure this takes time and if I’m doing it right, it will look kind of awkward, kind of ugly. When I get impatient and push the clay to be “pretty” before it is strong, it will collapse. I have to build it slowly and let it get stronger until it’s ready for the pressure needed to make the thin and delicate parts of the piece. This takes time and it’s not pretty. So, I think that mastery of a material isn’t as much avoiding the ugly phase as it is knowing what to do when the piece goes through the ugly phase. The more familiar you are with an artistic medium, the more you realize that the ugly phase is just a part of the process. The ugly is inevitable, but a master knows to keep going and push through it.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.nicolewoodbury.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/woodbury.nicole/